ACE Report: What’s Up with 350?

Open Google Doc of What’s Up with 350?

By Rebecca Anderson, ACE Director of Education

If you’re involved at all in climate action, chances are you’ve heard of an organization called 350.org. They’re a strong partner of ACE and they’ve led countless actions across the country, all with the goal of fighting climate change. But why are they named after a number? What does that number mean?

Where does 350 come from?

The number 350 comes from 350 ppm (parts per million), referring to a particular level of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Just for some points of reference:

- 400 ppm – where we are right now

- 280 ppm – where we were pre-Industrial Revolution

- 180 ppm – CO2 level during the last Ice Age, ~20,000 years ago

350 is the target level of atmospheric CO2 that we should aim for “if humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted.” This quote comes from a paper published last year by renowned climate scientist James Hansen and others called, “Target CO2: Where should humanity aim?”

Here’s where they get this number: Hansen et al. looked at paleoclimate data from past ice ages, as well as going way back into Earth’s history (60 million years ago). They looked particularly at those very touchy and all-important critters, feedback loops, and how they play a role on short-term (the next few decades) and long-term (centuries – 1000 years) climate.

Based on these long-term feedbacks, like ice-sheet melt, migration of vegetation as climate changes, and release of CO2 and methane from permafrost and ocean sediments, Hansen et al. conclude that we don’t want to be any higher than 350 ppm to keep life on Earth the way we’ve gotten used to it.

(For all the gory details, read the paper itself here.) So… this isn’t just a number he picked out of a hat. It’s got some good science behind it.

What’s it take to get to 350?

Hansen does also get into how he thinks we should get there, which includes ridding ourselves of all coal and sequestering (burying away) carbon already in the atmosphere – this brings us to the big problem:

Clearly, we’re already above 350 ppm.

And we’re going higher.

And we’re going higher at an increasing rate.

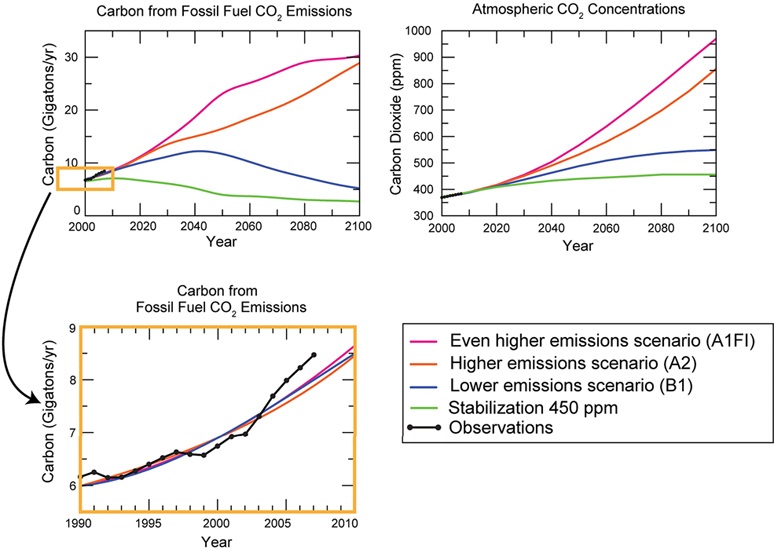

All the IPCC “future world” scenarios put us at at least 600 ppm up to 1000 ppm by 2100. Check out this graph on the EPA’s website here for CO2 possibilities over the next 100 years.

Here’s where the useful bathtub analogy comes in:

Think of the level of water in the tub as the amount of CO2 right now in the atmosphere. Right now, we’ve got the faucets turned on full-blast. To get the level to go down to where we want it (350), we not only have to turn the faucets completely OFF (ie, stop emitting any more CO2), we also have to pull the plug and drain out some of the water (ie, sequester some of that CO2 already up there).

I think a lot of people get confused and think that if we can stop producing as much CO2, that will mean the level of CO2 in the atmosphere will go down.

IT WON’T.

That’s like turning down the faucet a bit… there’s still plenty of water flowing into the tub. We’ve got to turn it off all the way. (Or almost all the way – The natural world can soak up some CO2 emissions without bad side effects, but that amount is pretty negligible to what we’re producing now.)

Is it possible to get back to 350?

Obviously, this is going to be really hard. It’s also too big an issue to really tackle here. Here’s how the SF Chronicle puts it, “350 or 450? There’s a split in scientific and political communities about which number…is the tipping point into dangerous climate change. Actually, it goes sort of like this: Most scientists agree that 350 is the more realistic number, but most politicians say 450 is the best we can shoot for.”

Hansen himself doesn’t even say we should be aiming immediately for 350, but that that’s where we should be heading towards eventually as a stable level, perhaps many decades from now.

So, what does all this mean?

Here’s my conclusion: 450 would be good. 350 would be even better. Because both of them are so far from where we’re headed in reality right now, it’s not worth squabbling over the details. Let’s just try to turn off (or down, as much as we can) that faucet as soon as possible!

Here’s one final quote from Gavin Schmidt, founder of RealClimate.org, as reported by Andy Revkin here:

“If you ask a scientist how much more CO2 do you think we should add to the atmosphere, the answer is going to be none.”

What’s Up with 350?

Student Worksheet

Name:

1. What does 350 refer to?

2. How much CO2 is currently in the atmosphere?

3. What’s the third option for dealing with climate change and what does it mean?

4. Who wrote the paper that called 350 ppm the target level of CO2? What kind of data did he use to derive this number?

5. Are we headed towards 350 ppm currently? If not, what level of CO2 are we headed to by the end of the century?

6. Use the analogy of a bathtub to explain the difference between CO2 levels in the atmosphere and CO2 emissions.

7. If people produce less CO2 in the future (but still some), will that eventually get us to 350 ppm?

8. What’s an alternative level of CO2 that politicians prefer?

9. BONUS: At current rates of emissions, when will we get to that level? (You’ll have to find out how fast CO2 is increasing in the atmosphere to do this.)